The Arabesque Table: Contemporary Recipes from the Arab World by Reem Kassis (Phaidon, 2021)

In one of his many letters to Gostan Zarian, his admiring younger friend Lawrence Durrell suggests a trip to Beirut: ‘it is at the foot of a huge mountain going straight up into the sky; there is the most fantastic valley [on] the other side called the Bekaa which you must see: and the mountains are rich with running streams and rock-doves.’ This language, some would argue Orientalist, evokes images of the ‘Paris of the Orient’ in the days gone by. Yet, while politically, Lebanon - as much of the Levant - is in turmoil, culturally, the fascination with the East has not gone away. Witness the British Museum’s exhibitions – Inspired by the East: how the Islamic World influenced Western art (2020) and Epic Iran (2021).

On this background, enter The Arabesque Table, published bang in the middle of the current pandemic, though conceived well before. In fact, more than a cookbook, it is a dedication to home and heritage by a Palestinian emigrant who studied in the US, worked in business, had children, and for years collected her family recipes in an act of recovering lost comforts. In this, Kassis is part of a now established tandem of ethnically diverse authors such as Olia Hercules and Tiko Tuskadze, who entered food writing as cultural anthropologists, rather than trained chefs.

For this, Kassis stands out – with the research, the historic note, and the argument she is making. Still calling herself a Jerusalemite, this compatriot of Edward Said’s, of this Holy City’s famous Armenian potters from Kütahya, recalls the first recipe books since cuneiform inscriptions, written by Arabs, charts the course of certain ingredients around the globe, and asks ‘What is national cuisine?’.

She maintains that cooking practices and foodstuff distribution are regional things (i.e. Mesopotamia), not conforming to political boundaries. They are also ethnic, she says, talking of Armenians ‘who live across the world but share the same cuisine regardless of where they are’ (though some may contest this claim of uniformity). On the other hand, culinary culture is fluid, Kassis says, and, somewhat counter-intuitively, may include products not native to lands. Think of tomato in Italian dishes, chillies in Thai, and cocoa in Swiss chocolate – all products native to Mexico and South America, which reached Europe and Asia after the Spanish colonisation of the Americas.

With that said, we are plunged into a book divided according to main ingredients (e.g. grains and pulses, or pomegranates and lemons) which flags up vegetarian, dairy-free and other recipes, cooking time and portion numbers. Among the staples like mutabal and fatteh, basturma and sujuk, which Armenians in the Diaspora and the Republic alike will recognise, we find shakshuka, in a nod to the Maghreb, the west of Arab countries. And no, we do not get into the ‘is shakshuka a Jewish dish?’ debate, in the spirit of the above-mentioned regional understanding of cuisine. After all, as Kassis says on another note, ‘We may think of shawarma and falafel as unique to the Middle East, but can you find one culture across the world that does not take a kind of meat or vegetable and wrap it in some form of bread?’

Lentil Bulgur Salad with Marinated Beet

There is no tagine recipe, but we have been warned that the book reflects the author’s personal connection to the Levant.

My own introduction to the Arab cuisine came a roundabout way, later in life. In post-Soviet Yerevan opening up to wider world (incidentally, I was studying Arabic then), there was the odd shawarma bistro, the best-known being in Tumanyan Street, which my friends and I frequented. Nevertheless, considering Armenia’s proximity to the Middle East, foodwise, the dominant imprint on my upbringing, excluding Armenian home cooking, was Soviet and Russian.

Shortly after the breakout of civil war in Syria, Arab food stores started opening in my native Yerevan. They sold za’atar and tahini and a plethora of other things. These were new ventures of Syrian Armenians who had fled the country that had provided a safe haven to their forefathers fleeing persecution in Ottoman Turkey almost exactly a century before. In time, with eateries like Zeituna or New Kessab, they would also transform the restaurant scene in Yerevan. As here in England, supermarket shelves and restaurant menus have been transformed by hummus and tabbouleh.

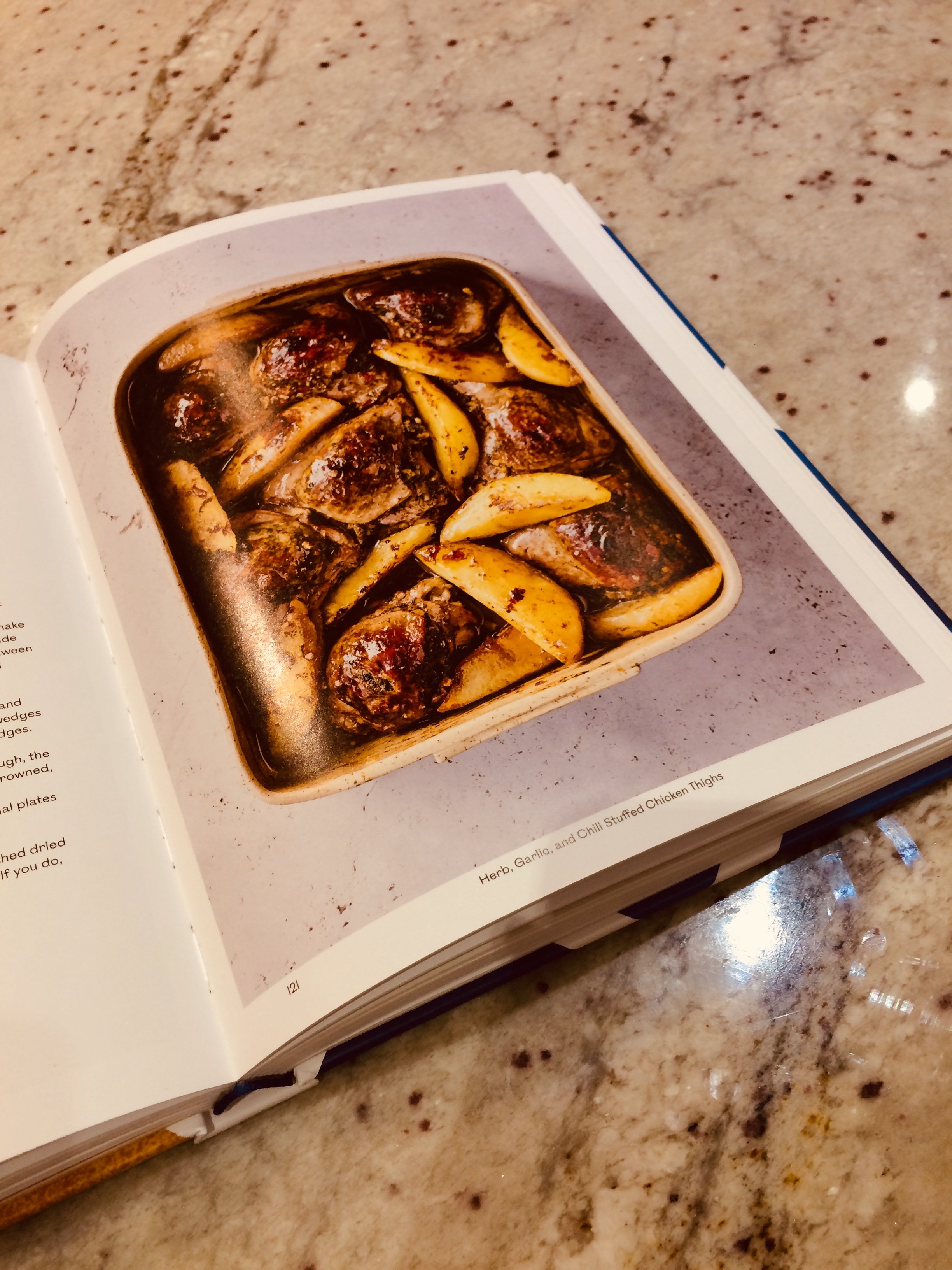

Herb, Garlic, and Chili Stuffed Chicken Thighs

From The Arabesque Table, I tried the Herb, Garlic, and Chili Stuffed Chicken Thighs, which smelled divine and looked appetizing, but had too much salt and chili and did not specify whether to cover the pan or not, so the end result had a lesser look but a rich taste and texture.

I also made the Lentil Bulgur Salad with Marinated Beet – a very wintry, substantial salad, which looked gorgeous and tasted good too. Here’s an extract from its introduction: ‘Overlooking the shores of the sea of Galilee, where the ancient city of Magdala once stood, now stands Magdalena, a restaurant named for the ancient city and birthplace of Mary Magdalene.’ Reminded of a lentil and raw beetroot salad that my mother makes, I had to stop myself from adding cumin seeds – an affliction to over-spice that may or may not pay off.

For armchair culinary travellers among you, looking for crossover with especially Western Armenian dishes, you will not be disappointed: a modern spin on a recipe for halaweh, or halva, awaits you. So does one on hareeseh, or harissa, a stew of wheat with meat. A variation of the latter from Armenia can also be found in Lavash by Kate Leahy et al.

A conservative when it comes to structure, I would have preferred to have chapters separated according to the daily meals (i.e. breakfast, lunch, and dinner) or types of course (starter, main, dessert), but the illustrations, the wealth of background information into the history of the ingredients, the exhaustive list of the source materials, and the easy-to-use index, make this criticism pale into insignificance. While my friends back in Yerevan complement their lahmajoon with kadayif, I am eyeing up the Reem Kassis Lemon Rosemary Semolina Cake – a variation on the Italian torta I once had at a Sicilian restaurant in London. But then, as was said before, whose recipe and where from is an ever-moveable feast.

Written by Naneh Hovhannisyan for “Breaking Bread With Neighbours”, a short series on culinary culture across the region.

Naneh grew up as a closet gourmand in the latter days of Soviet Armenia. She prides herself on taste - also called ‘gustatory’ – memory, and on her ability to survive on rounds of strong coffee alone. Cooking is for her an act of resistance, creativity and indulgence. She lives in England with her family, and in the time left from selling books for a living, tries to read them for pleasure.