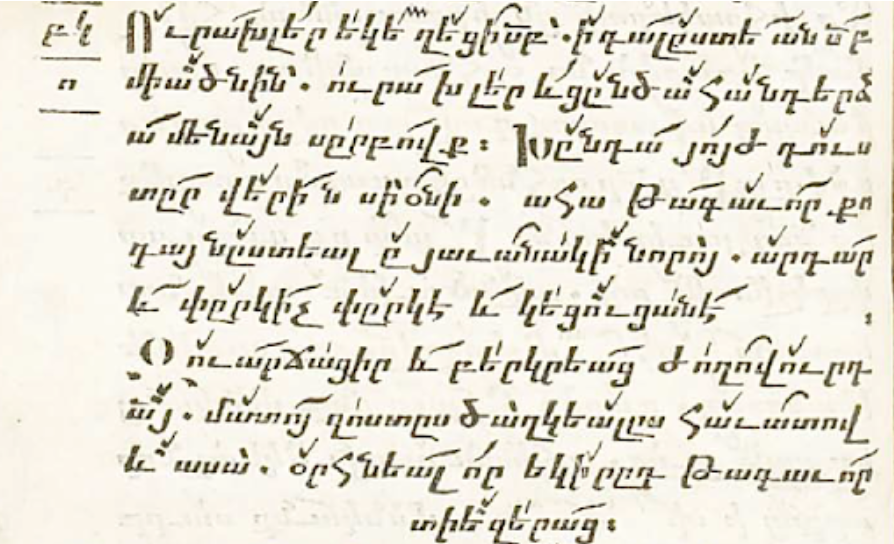

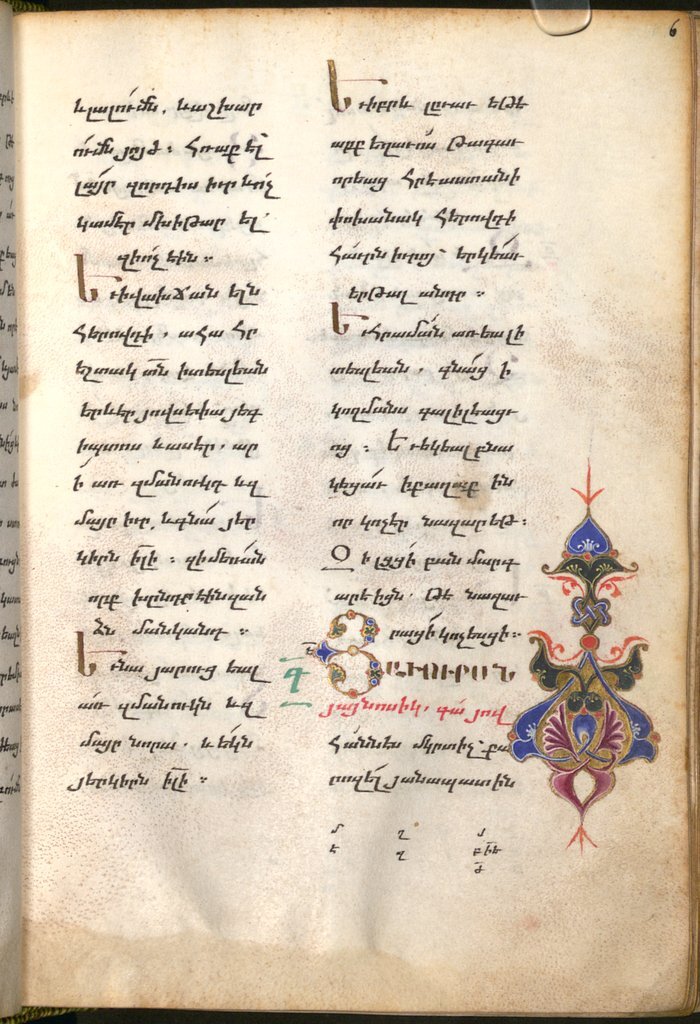

Languages are like living organisms – they evolve. Through fossils scientists are able to trace the evolutionary paths of animal and vegetable life. For linguists, on the other hand, texts are the ‘fossils’ through which they are able to study the evolution of a given language. Very often we come across the adjectives ‘old’, ‘middle’ and ‘modern’ describing the relative age of literary languages. As a written language since the creation of its alphabet in the early 5th century, Armenian is no exception. Armenians call their old language Grabar, meaning the ‘written language’. In English this is often rendered as ‘Classical Armenian’, ‘Old Armenian’ or ‘Ancient Armenian’, although strictly speaking the term ‘Classical’ should only apply to the period immediately after the invention of the alphabet until the middle of the 5th century. The monk Mashtots invented the Armenian alphabet in order to translate the Scriptures and make them available as widely as possible to enable the new creed of Christianity – barely a century after it was made the state religion – to take hold amongst Armenians. To this end, the Bible and other sacred texts were quickly translated into the variant of the language most widely spoken and understood.

As the old Armenian literary language, Grabar had been in use from the 5th century well into the middle of the 19th century. It can still be heard chanted and recited during Armenian church services. By the 11th century Grabar had ceased to be a spoken language, but like Latin, continued to be used in official texts, theological, historical and scientific treatises. The Mekhitarist Order, the tireless pioneers of Armenian Enlightenment in Venice and Vienna, made valiant efforts to maintain Grabar as the literary language. However, it was supplanted in the 19th century by the vernacular language, codified into two literary variants of East and West Armenian in the Caucasus and Constantinople, respectively.

Like the two variants of Modern Armenian, Grabar was an inflected language involving modification of words to express different grammatical functions. Grabar had a very rich vocabulary characterised by a vast range of synonyms and idiomatic expressions, many derived from the popular language of a bygone age. Grabar benefitted greatly from the Greek language between the 6th and 8th centuries when many Greek philosophical, theological and grammatical texts were translated by Armenian scholars who had studied in centres of Greek culture, such as Constantinople, Alexandria and Athens. These translations introduced many newly coined words and expressions, together with new arrangements of words in sentences following the Greek model. Some of these neologisms were rejected in later centuries, but many remained and greatly enriched the Armenian language.

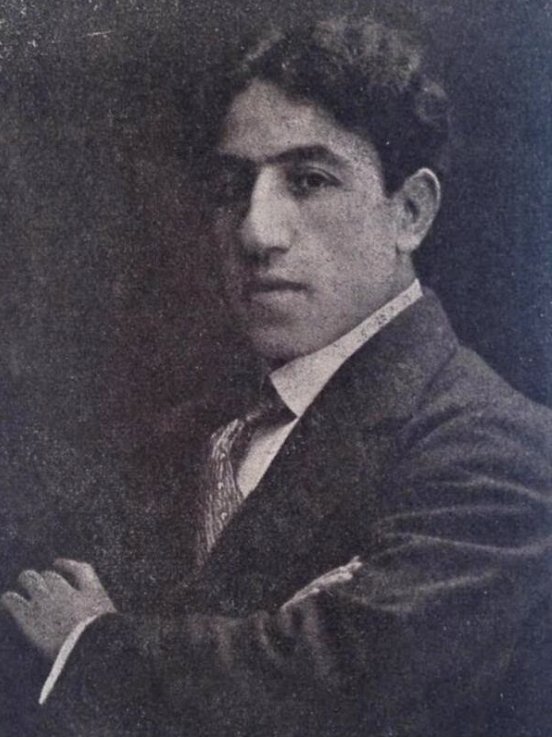

In addition to the bulk of translated works right after the invention of the alphabet, Armenian authors also created original works. Koriun’s biography of his teacher Mashtots is considered to be the first book written in Armenian. To my knowledge, the most recent original piece written in Old Armenian was by an Englishman. Charles James Frank Dowsett composed an Armenian ode for Sir Harold Bailey, his mentor and lifelong friend, to celebrate Bailey’s ninetieth birthday in 1989. Dowsett was the first Calouste Gulbenkian Professor of Armenian at Oxford and built an extensive collection of books on Armenia and neighbouring peoples. The Armenian Institute is fortunate to be the custodian of the library of this latter-day poet who wrote in Grabar.