The Armenian Diaspora has been present for over 1,500 years. Armenians have helped build communities in their respective host countries, while preserving their culture outside of their borders. In return, they have welcomed other cultures within their homes, cuisine, and all walks of life.

Although the Armenian Diaspora has existed for almost two millenniums, we’ll be directing our attention towards the population and the music scene of the 20th century, which was formed after World War I as a direct result of the Armenian Genocide. Large-scale and systematic massacres took place against Armenians in their ancient homeland, which, at the time, was under the control of the Ottoman Empire. The Young Turks, a new Turkish ultra- nationalist party that took control of the Ottoman Empire, put into play the beginning of what they thought was the final solution to the Armenian "problem." Over a million and a half Armenians were exterminated through starvation, death marches, and concentration camps set throughout the Armenian Highlands and the Syrian Desert. This genocide began in 1915 and ended in the early 1920s, after the Armenians in Eastern Armenia (present-day Armenia) collectively fought off the final wave of Turkish forces, which were set on killing every single man, woman, and child. During the final days of the Armenian Genocide, the First Republic of Armenia was established. However, the dream of a free and independent republic did not last long, as a ravaged nation became the newest addition to the region’s Sovietization.

Although the genocide did not officially begin until 1915, anti-Armenian sentiments and massacres had been occurring since the late 19th century at the hands of the Ottoman Turkish government. With the inclusion of the statewide massacres from the 1890s all the way through the early 1920s, including the Armenian Genocide, nearly 2 million Armenians fell victim to the Ottoman Turks. Many historians claim that roughly 2 million Armenians lived in Western Armenia (Modern-day Eastern Turkey) and that roughly 300,000 had survived the Armenian Genocide. This compilation will tell a fraction of the story of the direct descendants of these tragedies.

The survivors of the Armenian Genocide settled in countries such as Syria, Lebanon, France, Russia, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Ehtiopia, Sudan, India, Australia, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. Survivors who stayed in the First Republic of Armenia lived through the Sovietization of the country. Fast-forward a few decades and you’ll come to find that Armenians in the Diaspora have been thriving. They’ve built schools, churches, community centers, restaurants, and much more. There are professionals of all sorts, businessmen and businesswomen of all trades, painters, sculptors, actors and actresses. However, the wounds of the genocide were still open within Armenian music up until the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Folk bands are being formed, soul groups are emerging, and Estradayin singers (the Armenian genre equivalent to French Chanson) are gracing their respective stages. The Armenian Diaspora is at the cusp of two worlds; the Western world that revolves in the countries they’ve settled in and the Eastern world that they come from. There’s a harmony of cultures, cuisine, fashion, and music. This unification between worlds is where the musicians in the Armenian Diaspora began to make their mark. A lot of stars were introduced and praised, but there were many artists who didn’t receive the attention they deserved.

Between the 1970s and 1980s, another crisis hit the Armenian Diaspora. This time, it occurred in the Middle East. A vicious civil war erupted in Lebanon in 1975 and lasted until the early 1990’s. While the war was mainly between all sorts of different factions, the Armenians were preparing for the worst in their neighborhoods. Mainly concentrated northeast of Beirut, the Armenians of Bourj Hammoud, a small, yet tight- knit town secured the perimeter of their community. They protected their kin as the Lebanese Civil War threatened the existence of Beirut’s Armenian community. Many young Armenians took arms to defend it from opposing forces, which wanted to control Bourj Hammoud and possibly rid all of its inhabitants.

Although the war took a heavy toll on Lebanon, the Armenian community of Bourj Hammoud picked itself up, but slowly began to depopulate, as civilians began to emigrate to North and South America, Australia and Europe. Despite the turmoil, record labels, such as Voice of Stars, released music and held concerts in Bourj Hammoud. The music spread throughout the Armenian communities in the Diaspora and within the Lebanese artistic communities. Artists such as Adiss Harmandian, Ara Kekedjian, Vatche Yeramian, and Marten Yorgantz were labeled as “pop stars”. They each had a unique approach to their work, combining the western sounds of disco and soul with Armenian folk elements, paving the way for a rising Armenian music scene in the Diaspora. Other musicians such as Ihsan Al-Munzer, Fairuz, Ziad Rahbani, and the other Rahbani Brothers, frequently collaborated with Armenian producers from Beirut. Daniel Der Sahakian, Jacques Kodjian, and Khatchik Mardirian are the most notable producers and arrangers from Lebanon of Armenian descent. Daniel Der Sahakian still resides in Bourj Hammoud and operates Voice of Stars until this day. Jacques Kodjian left for the United States during the Lebanese Civil War. He worked with Adiss Harmandian in Los Angeles and operated with other Armenian groups in New York City. Khatchik Mardirian produced well sought-after records with Ziad Rahbani on their record label, Zida. Unfortunately, Mardirian passed away in 2013, however, his son Diran runs Chico Records in Beirut, which was once Khatchik’s store. As the war progressed, the production of music in Lebanon continued as well. An enormous catalog of music can be dug up from the time period of the war.

In Bourj Hammoud, producers and artists were constantly recording in the midst of bombs dropping in their streets and on their roofs. Armed volunteers would secure the perimeter of the small Armenian inhabited town, but there were unfortunate occurrences that would take place from time to time. Besides these instances, the people of Bourj Hammoud tried to continue their lives as normally as they could. As for the musicians, their main career objective was to uphold consistent creativity while preserving their identity and surviving the war. One of the best ways to do so was through music and the arts. Artists featured in this compilation such as Ara Kekedjian, Adiss Harmandian, Haro Pourian, Eddy Jeghelian, and Setrag Ovigian, toured the Middle East even during a time of war. The nightclubs and venues in Bourj Hammoud kept their doors open. These establishments were a place of freedom from the lingering threat of disaster and a place where a rich culture could have a live platform.

Eventually, Armenians from Lebanon emigrated to Syria, France, Australia, Canada, and the United States. In France, Armenian artists settled in Paris and Marseille. The most popular Armenian artist in France was the late Charles Aznavour, however, Marten Yorgantz was the center of attention in terms of French-Armenian disco and boogie. He incorporated the sounds of his Armenian heritage with a French touch from the late seventies until the mid eighties. After working closely with Daniel Der Sahakian in Lebanon, Marten Yorgantz produced records with Claude Salmieri, as his engineer and independently released his records in the early 1980s. This proved to be Yorgantz’s rise to prominence in the Armenian discotheques of France. Marten Yorgantz toured and still tours in the United States, Canada, France, and Armenia to this day.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Armenian community in the United States began to grow as a result of the Lebanese Civil War, Iranian Revolution, and the dwindling Soviet Union. The majority of newcomers settled in Los Angeles County, concentrated in cities such as East Hollywood, Glendale, Pasadena, and Montebello. Before this influx of immigrants, there was a well-established record label called Parseghian Records, located in an area of East Hollywood, presently referred to as ‘Little Armenia’. It was run by the late Kevork Parseghian, who was a hardworking and driven Armenian- American. He had escaped from the Middle East with his family, who were witnesses of civil wars and genocide. Parseghian Records was originally Parseghian Photo; people would take their passport photos there (and still do). It wasn’t until Kevork had customers frequently request that he duplicate their cassette tapes for them, which sparked the idea for Parseghian Records. As Armenians began building communities in the states, Parseghian Records catered the soundtracks to their constructions. The most notable artists who released music through Parseghian were Paul Baghdadlian and Harout Pamboukjian. After settling in the United States, Baghdadlian and Pamboukjian were quickly labeled “The Kings of Armenian Pop”. Parseghian Records opened its doors in 1948 and since then, it has been the largest producer and distributor of Armenian music in the world. One can find Parseghian Records still operating today in Los Angeles by Kevork’s son, Dan Parseghian.

Although Harout Pamboukjian released a couple of his acclaimed albums with Parseghian Records, his first and second studio albums were released with Pe-Ko Records and Arka Records. His first record Oour Eyir Astvats (Where Were You, God?), referring to the tragedy that was The Armenian Genocide, was a huge success. However, it did not resemble most of his catalogue and trademark sound. Not to mention, it was recorded by Pamboukjian and his band at Quad Teck Studio in Los Angeles only two months after moving to the states. Pe-Ko Records, also located in Los Angeles (but originally from Canada), now operates as Hollywood Music Center. The founder, Movses Panossian, was raised in Bourj Hammoud, surrounded by many producers and musicians in the area before and during the Lebanese Civil War. Panossian was influenced by traditional Armenian and folkloric Arabic music, as well western Pop and Soul. Although Panossian took pride in his work as a barber and a tailor, music was his true calling. When he moved to Los Angeles in 1981, he began to sell jewelry just to make ends meet, but he soon started his label out of passion for the music. He focused on releasing Armenian and Arabic music, working with artists who soon became legends. Panossian worked with Harout Pamboukjian. Other notable artists he worked with who reached great heights in their respective scenes were Paul Baghdadlian, Setrak Sarkissian, Hassan Abou El Seoud, and many others. Movses Panossian’s work and contribution to the Armenian and Arabic music scenes are celebrated till this day. His son, Mher Panossian, has continued the family business while working with contemporary artists from Armenia and The Middle East. As previously mentioned, after a couple of weeks of being in the States, Harout Pamboukjian was tirelessly working on his debut album, Our Eyir Astvats. Coincidentally around this time, Pamboukjian’s close friend and musician, Avo Haroutiounian had moved to Los Angeles from Yerevan with a brief stint in Beirut, but ultimately left for Los Angeles due to the Lebanese Civil War. The two reconvened by a stroke of luck on the corner of the Parseghian Records office in 1976. During this encounter, Pamboukjian asked then 19-year-old Haroutiounian to play the violin and assist with the songwriting on his debut album. The album took off and Harout Pamboukjia became an overnight sensation. Two years after his work on Pamboukjian’s debut record, Avo Haroutiounian befriended Kevork Parseghian and began producing his very own album. In January 1979, Haroutiounian released his first and last solo album, Sunrise, via Parseghian Records. Haroutiounian never went on to make more solo records because he didn’t feel comfortable with his vocal abilities. He believed his true talents lied in songwriting and production. Sunrise was ahead of its time in terms of production and songwriting regarding Armenian records. It’s a pity that Haroutiounian didn’t go on to make a second solo album. This didn’t mean that he had stopped making music. After the release of Sunrise, Harout Pamboukjian asked Avo Haroutiounian to produce his records, assist with songwriting, and to play bass on upcoming tours. Haroutiounian went on to produce a handful of Armenian records in the 1980s, but his most notable works have been completed for Pamboukjian. He continues to work with Pamboukjian until this day, well into his 60s. After interviewing him in January 2019, it's safe to say that nothing will stop him from producing and touring with Harout Pamboukjian. He will go down in Armenian music history as one of the hardest working musicians behind the scenes.

Between 1978 and 1979, Iran had gone through an Islamic Revolution, which ultimately overthrew a monarchy that had lasted for the greater part of the 20th century. For centuries, Armenians had lived in cities of Iran, such as Isfahan, Julfa, and Tehran. During the Armenian Genocide, 50,000 Armenians found refuge from The Ottoman Empire in Iran. Although diplomatic and civic relations with Armenia were positively stable in the 20th Century, and continue to be, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 threatened the safety and constricted the liberty of Armenians in Iran, as it did with much of the general population. During the Islamic Revolution, an Armenian composer by the name of Jozeph Sefian, more commonly known as Jozeph, was making records that were ahead of his time. He was born and raised in Aligudarz, Iran in 1943. He was drawn to music from a young age, picking up the guitar and drums as he grew up, but he realized his true passion was to sing and write music. From the late seventies until the mid eighties, Jozeph frequently visited Los Angeles to work with Kevork Parseghian. He released all of his work with Parseghian Records and even befriended the rising pop star, Paul Baghdadlian. He worked with some of the best musicians in Iran at the time such as Andre Arzoumanian, Edward Yarkhoda, and Haykaz Abrahamian. Although his music was released in Los Angeles via Parseghian Records, it’s important to note that he recorded all of his work in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution. Jozeph and all other artists were not allowed to perform in Iran at the time, however he was granted permission to tour the United States and the United Kingdom. He also performed at a charity concert for those affected by the 1988 Spitak earthquake in Soviet Armenia. Jozeph was allowed to move to the United States in 1997 to join his family. By then, his health began to dwindle and he began to focus more on spending time with his family and friends. Unfortunately, he passed away in the spring of 2006.

The Armenian Diaspora’s adoption of their new homes in the western world did not deter the preservation of their language, culture, and music. Their path reflects the height of the Great Silk Road which connected the Eastern and Western worlds; Armenia serving as one of the primary bridges. After the fall of the Soviet Union and the ‘Iron Curtain’ in 1991, academic and public interests were raised to further excavate the cultures of the former Soviet republics, which Armenia was a part of for seven decades. Armenia was the bridge that connected Europe and Asia, and during the time of the Silk Road, Armenians were introduced to spices, silk, and other commodities that benefitted ordinary people and the country at the time. In return, Armenian merchants introduced new products in their respective markets. As archeological and historical evidence shows, Armenians began to wear clothing made of silk from China, cooked with spices from India, and dined with pottery from Persia. Armenians utilized silk from China and mastered the craft of rug making. Traditional Armenian rugs had appeared in all types of buildings in Armenia, later appearing in homes located as far as Java and Great Britain. The western world was reigning its presence in the eastern world, but interestingly enough it was at this time that the eastern world found comfort in the west. The same can be said about the tracks I have presented in this compilation and in other types of Armenian genres.

The Armenian Diaspora welcomed the music of the west in their homes just as the people of the west welcomed them in their respective countries. From the 1960s until today, Armenian music from The Diaspora has an evident element of the west chiseled into it. From the 1970s to the 1980s, jazz composers in the USSR and pop singers in the Diaspora had combined traditional harmonies with heavy drum breaks, funky bass lines, and impressive keyboard skills. It didn’t matter if the more prominent artists were doing it or if the lesser-known artists had adopted it. The fact of the matter is that these artists were able to express themselves and experiment in ways that, at the time, were viewed as avant-garde to the Armenian public.

Some artists gained recognition and fame from these types of works, but many weren’t so fortunate. Although most of these artists toured Europe, The Middle East, and The Americas; typical concert-style venues and nightclubs weren’t the live platforms of choice. Instead, the Armenian-style banquet halls were and still are the favored venue for these artists. Similar to all other citizens of the world, the Armenian Diaspora would look forward to the weekends, because this is when they’d have the chance to see their favorite Armenian musicians perform in an intimate setting, where everyone would gather to eat, drink, and dance. The Armenian Banquet Hall was essential since most venues wouldn’t book Armenian artists, unless they were rented out.

During the period in which the majority of the tracks from this compilation were released, the Armenian diaspora paid no mind to them. Instead, they focused their attention toward “mainstream” Armenian and internationally acclaimed pop records of all sorts. Some knew about these records, but they initially thought it was too obscure for their liking. Some merely recall the artist’s names, while many haven’t heard of them at all. The majority of Armenians in Armenia weren’t aware of these works when they were originally released, due to the strict control of music in the Soviet Union, which may also be the reason why these records cannot be found in Armenia today. Although jazz was popular and promoted in the USSR, the tracks from this compilation were outlawed in Armenia at the time. Sure, there were a few underground groups that had formed in Soviet Armenia in the late seventies and gained somewhat of a cult following, and more popular records were smuggled in limited quantities, but ultimately, the Soviet authorities found this music style unconventional. The reason why jazz, classical, and some traditional folk music were popular in Soviet Armenia and the rest of the USSR was because the state had sanctioned and backed the artists to produce those sorts of records.

Growing up as an Armenian in Los Angeles, I listened to a few of these tracks and many of the artists but something in me wanted to dig a little deeper. Naturally, being a collector of records and an admirer for the sounds of the seventies and eighties, I began to meticulously dig through crates upon crates in a number of different countries to find these Armenian cuts. I thought to myself, “Well, if other nationalities and cultures have disco records, then surely we must.” This task proved to be difficult, as there aren’t that many out there. This very question pushed me to work on this compilation for three years, from 2016 until 2019. Ironically, a few of the tracks on this compilation were recorded in Los Angeles, but I had no luck finding them here.

Besides crate digging in LA, I found many of these tracks while digging in the Middle East and in a few countries in Europe. The process of collecting the tracks was the most challenging part, because the majority of these records were pressed in a limited quantity during the time of their release. However, this made finding them some of the most rewarding moments of my investigation. To find these records in person and to physically hold them in my hands after years of endless digging brought me so much joy. It allowed me to amplify sounds and stories that were forgotten and ultimately share them with the world. I hope collectors and contemporary DJs find this compilation enjoyable as it sheds light on a host of Armenian obscurities. The reintroduction of these tracks and these artists alongside their stories has been a goal of mine for a while. For me, it has become a story of survival through revival. Not only does it tell the story of a testing journey for the Armenian Diaspora through music, but it’s also packed with various musical ingredients, ranging from traditional sounds to an attractive and westernized approach to music production.

From the culmination of sounds of the near east and the west, to the struggle of finding a new home on the other side of the world, the Armenian Diaspora recorded powerful music -- some melancholic, but many jubilant. The Armenian people gathered together with the goal to survive, and all the while ended up thriving. They built new communities, respected their new neighbors, and loved to live. They adopted the customs of the new world and embraced them, yet never forgot their identity or their roots. The present state of Armenia may be small, but the Armenian nation as a whole remains large.

This record is dedicated to the victims of the Armenian Genocide and victims of all Genocides and systematic racism that have occured throughout history and continue to this day. The actions of ultra-nationalists of the past cannot be ignored, as their actions and crimes perpetuate to this day through their successors around the world. Stand up, speak up, and fight the good fight!

Written by Darone Sassounian for Terrestrial Funk.

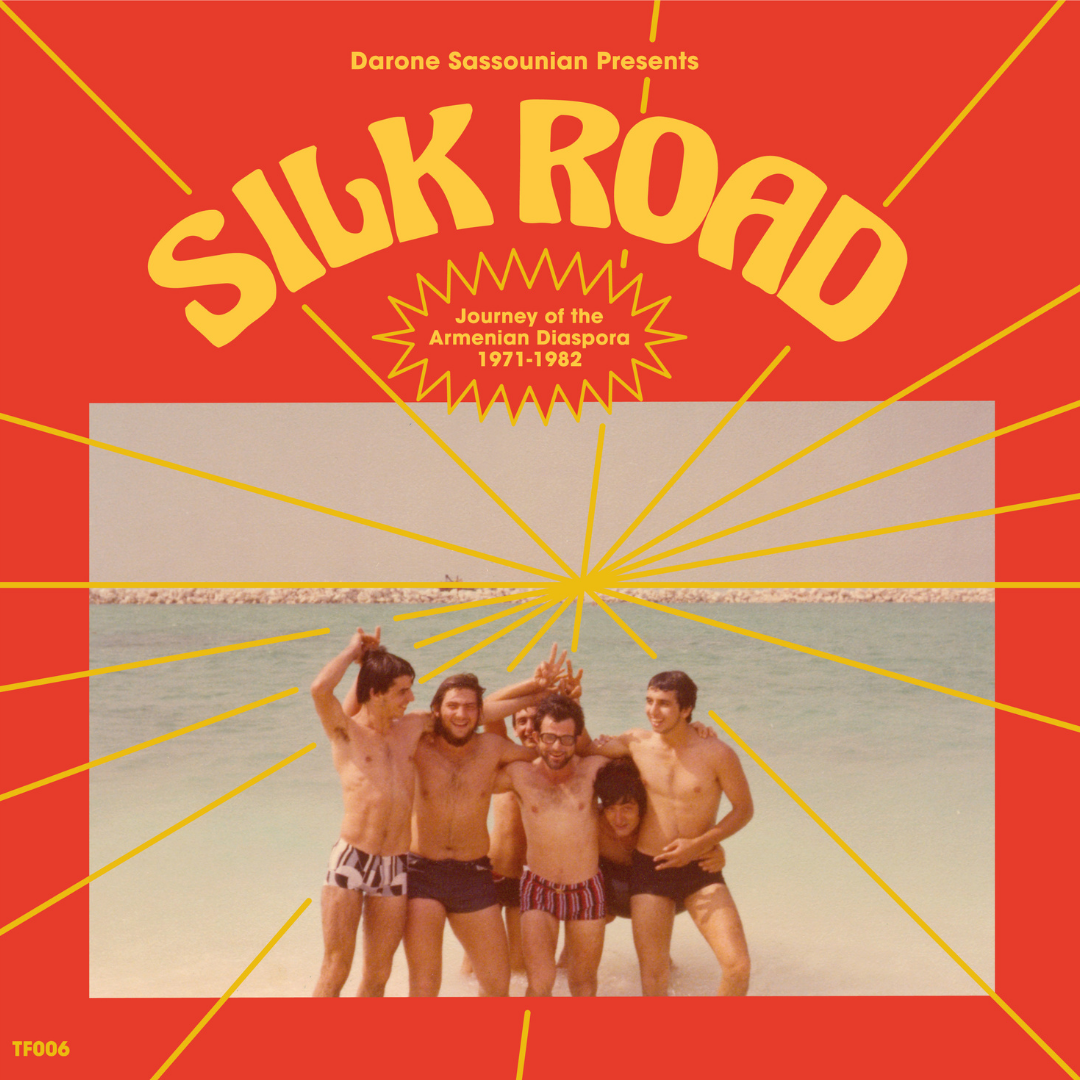

Darone is a DJ, selector, and producer from Los Angeles. He runs the indie artist management and booking label, Rocky Hill. Sassounian focuses on bringing an array of sounds into the world - ranging from styles introduced to him at an early age, to sounds he sought after later on. Darone released his full length compilation; "Silk Road: Journey of the Armenian Diaspora (1971 - 1982)" via Terrestrial Funk on February 22, 2021.

Compiled by Darone Sassounian, who spent three years tracking down the records and artists through crate digging across LA, the Middle East and Europe; fulfilling a calling to lift his people’s voice, a people that have always faced the threat of erasure. The music was made a generation after the Armenian Genocide, a testament to perseverance. The seven tracks featured are incredibly inventive and unique in their interpretations of Western seventies sounds.